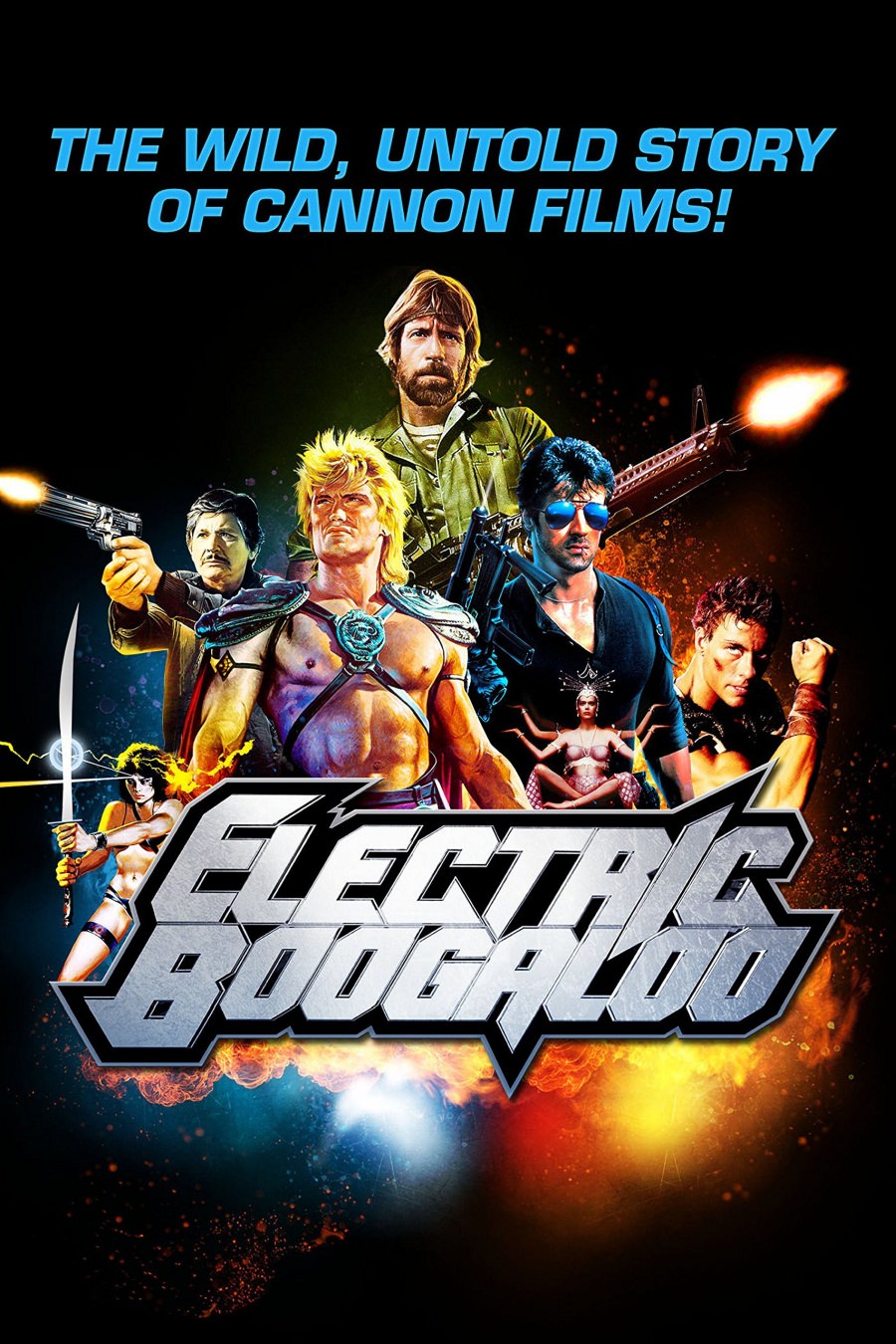

Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films

Directed by Mark Hartley (2014) ***

It’s uncertain why the lapse of time gives some pop culture detritus more entertainment or sociological value than it originally had when created. It may because the work can be looked at in a new way now, in context; it can be appreciated for the ways it expressed (even if poorly) the concerns of its age. It may because it had elements that were ahead of its time. It may just be because the trash, instead of being thrown away, somehow survived in its initial, shiny, gaudy magnificence. Mark Hartley’s propulsive documentary on the rise and fall of Cannon Films gives a fresh look on a library of films this viewer mostly ignored when they were released. Some of the Cannon films bear re-investigation, though, while others look so bad as to be fascinating.

It’s uncertain why the lapse of time gives some pop culture detritus more entertainment or sociological value than it originally had when created. It may because the work can be looked at in a new way now, in context; it can be appreciated for the ways it expressed (even if poorly) the concerns of its age. It may because it had elements that were ahead of its time. It may just be because the trash, instead of being thrown away, somehow survived in its initial, shiny, gaudy magnificence. Mark Hartley’s propulsive documentary on the rise and fall of Cannon Films gives a fresh look on a library of films this viewer mostly ignored when they were released. Some of the Cannon films bear re-investigation, though, while others look so bad as to be fascinating.

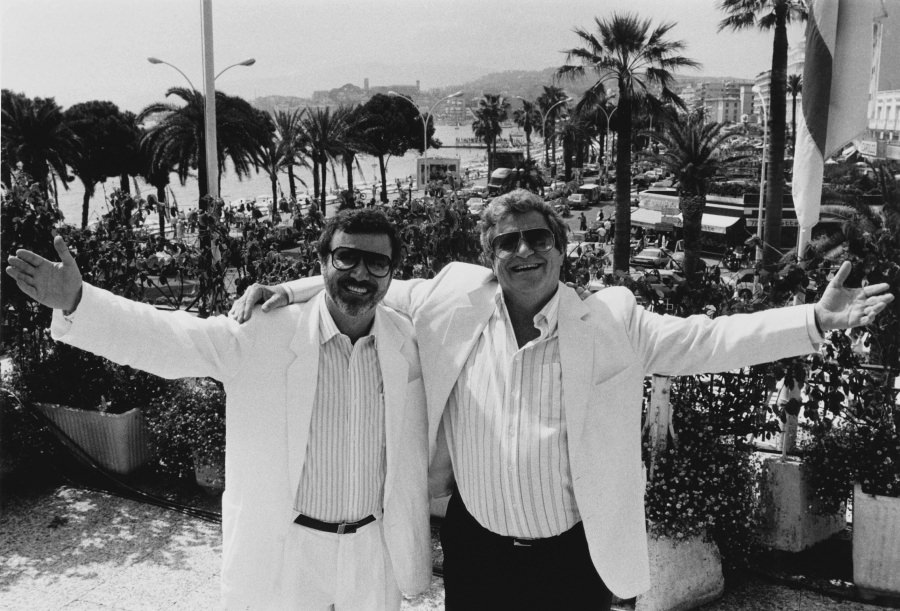

Though Cannon Films was founded in the ’60s as a distributor of soft porn Swedish titles, as well as the producer of more serious fare like Joe (1970), starring Peter Boyle and Susan Sarandon, it wasn’t until the company was sold to two movie-obsessed Israeli cousins, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, that the company really took off. Globus was the duo’s producer and businessman; at the age of five he had been helping his father, who owned a cinema. Golan was the film director and writer, who had studied filmmaking at New York University in the ’40s and worked as an assistant to film producer Roger Corman, the so-called “Pope of Pop Cinema”.

The enormous success of Golan and Globus’ 1978 Western German/Israeli sex farce Lemon Popsicle (weirdly remade in the U.S. as The Last American Virgin) showed a path forward for the producers, but action movies soon took over as their main concern. In the meantime, Golan wrote, directed and produced what looks like a jaw dropping travesty, the disco-soaked science fiction musical comedy biblical allegory The Apple, now considered to be one of the worst films ever made (and described by one critic as a “cut-price extravaganza [that] plummets to a new low in opportunistic inanity”).

Once the cousins acquired Cannon Films (and especially after they attained a distribution deal with MGM), they had the resources to make big films, many films, and they funded them, patched them together, promoted them and got them onscreen with a relentless zeal and drive that would make any budding entrepreneur dizzy. They did without the Hollywood niceties (expensive lunches, etc.) to have the time and money to make more films. They would create promotional posters and pre-sell films to foreign markets — films that didn’t yet exist, films which didn’t even have a screenplay, advertising actors who hadn’t yet been signed. When making the abysmal Captain America (released directly to video through Golan’s 21st Century Film Corporation) Golan reportedly funded the ongoing production with suitcases of money filled by foreign investors, then transferred to the production site in Yugoslavia. (The screenplay was never completely filmed; director Albert Pyun complains they had to skip filming the action sequences.)

Once the cousins acquired Cannon Films (and especially after they attained a distribution deal with MGM), they had the resources to make big films, many films, and they funded them, patched them together, promoted them and got them onscreen with a relentless zeal and drive that would make any budding entrepreneur dizzy. They did without the Hollywood niceties (expensive lunches, etc.) to have the time and money to make more films. They would create promotional posters and pre-sell films to foreign markets — films that didn’t yet exist, films which didn’t even have a screenplay, advertising actors who hadn’t yet been signed. When making the abysmal Captain America (released directly to video through Golan’s 21st Century Film Corporation) Golan reportedly funded the ongoing production with suitcases of money filled by foreign investors, then transferred to the production site in Yugoslavia. (The screenplay was never completely filmed; director Albert Pyun complains they had to skip filming the action sequences.)

Hartley, who also directed Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation (2008), keeps this nearly hard-to-believe story racing forward, almost as if he’s trying to keep up with Golan and Globus’ crazy schemes, bold gestures and far-out methods of getting product to movie screens. Along the way he interviews Frank Yablans, the previous CEO of MGM, who doesn’t bother to hide his contempt for the films Cannon provided for distribution, Boaz Davidson, producer of some of the worst films I’ve seen, and some actors who had the opportunity (and sometimes misfortune) of starring in Cannon films: Molly Ringwald, Elliot Gould, Richard Chamberlain, Bo Derek and Robert Forster.

Cannon Films, whose trailers were announced by the sound of cheesy synthesizers, became known for one-note, explosive, gratuitous violence and action tales. Attaining the rights to Charles Bronson’s 1974 Death Wish, they made three sequels with Bronson. Chuck Norris made a trilogy of films. Their 1981 Enter the Ninja, which recouped fifteen times the cost of making it, spawned two sequels. Cannon made pizza delivery guy Jean-Claude Van Damme a star in a series of films.

Cannon was also noteworthy for making one of the first hip hop movies, Breakin’ (1984). (The ridiculous sequel was titled Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, hence this documentary’s name). Cannon was also, surprisingly, instrumental in giving indie and outsider directors free artistic reign, hiring and distributing work by artists like Roman Polanski, Jean-Luc Godard, Franco Zeffirelli (who has only good things to say about his experience), Norman Mailer and John Cassavetes.

Cannon was also noteworthy for making one of the first hip hop movies, Breakin’ (1984). (The ridiculous sequel was titled Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, hence this documentary’s name). Cannon was also, surprisingly, instrumental in giving indie and outsider directors free artistic reign, hiring and distributing work by artists like Roman Polanski, Jean-Luc Godard, Franco Zeffirelli (who has only good things to say about his experience), Norman Mailer and John Cassavetes.

The film-making duo eventually lost ownership of Cannon in the late ’80s due, in part, to over extension of financing for films promoted but not yet made. Though they were no longer the combined force they had been, their legacy had one last laugh. Such is the competitive spirit of Golan and Globus that when they discovered this documentary was being made, they sped into production, and beat to the marketplace, their own (less well received) documentary on Cannon films, The Go-Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films.

The Warner Bros. DVD presentation of Electric Boogalo includes 25 minutes of quite entertaining deleted scenes and a wealth of original trailers for Cannon films. Warning: Because some of the company’s films are casually exploitational, the documentary is decidedly NSFW.

—Michael R. Neno, 2022 Apr 25