Louis Feuillade’s Fantômas

Fantômas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine (1913) ***1/2 / Juve vs. Fantômas (1913) **** / The Murderous Corpse (1913) **** / Fantômas vs. Fantômas (1914) **** / The False Magistrate (1914) ***

Many of those who consider themselves fans of classic films would react to the name of Louis Feuillade with a blank stare. The obscurity is undeserved. Feuillade was a master filmmaker at a time (pre-WWI) and place when his country, France, was the worldwide center of cinema. He wrote and directed so many films the exact number seems to be unknown: between 600 and 800. He oversaw and excelled in widely diverse (and contradictory) genres and film movements, pioneering new genres and techniques. And yet, there are no biographies of Feuillade in or out of print that I can find, and in-depth information about him is scarce.

Many of those who consider themselves fans of classic films would react to the name of Louis Feuillade with a blank stare. The obscurity is undeserved. Feuillade was a master filmmaker at a time (pre-WWI) and place when his country, France, was the worldwide center of cinema. He wrote and directed so many films the exact number seems to be unknown: between 600 and 800. He oversaw and excelled in widely diverse (and contradictory) genres and film movements, pioneering new genres and techniques. And yet, there are no biographies of Feuillade in or out of print that I can find, and in-depth information about him is scarce.

Made the Artistic Director of the first and oldest film company in the world, Gaumont, in 1907, Feuillade wrote manifestos detailing the different sorts of films he wanted Gaumont to make: “Le Film Esthetique” — highbrow, historical and fantastical films, often with gargantuan sets, flamboyant costumes and pageantry; “Life as It Is”, an early attempt at realism in film; and comedy. Feuillade directed two very popular series of films starring young children, the Bébé Apache series — around 90 films — and the Bout de Zan series — around 62 films). His next, groundbreaking initiative was serialized crime films, dreamlike, evocative adventures which had a big impact on later filmmakers like Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock and Claude Chabrol, and are still influential today (see the Batman films of Christopher Nolan). These series include Fantômas, Les Vampires, and two Judex projects.

Watching Feuillade’s crime serials today is like seeing the primeval origins of what we now think of as “pulp”. Judex alone creates the template for the masked, costumed, mysterious hero with a secret identity, the template later used for The Shadow, Zorro and Batman (to name just a few). Les Vampires and Fantômas revel in sheer evil; their stories center around criminals. The five films of Fantômas total nearly six hours of watching (longer in their original prints). Viewing them is an immersive experience. For all their contrivances and static directing (more on that later), the series is imminently watchable, the content fascinating, the situations often morbid and suspenseful.

Fantômas (René Navarre) is a master of disguise, a master criminal, and a ringleader of the underworld. He can insinuate himself into society playing whatever role suits his needs at the time: a lover, a judge, a doctor, a prisoner. He treats his underworld comrades as cavalierly as he does the upper crust, stealing from them with impunity. Determined to catch and bring Fantômas to justice are Inspector Juve (Bréon), of Paris and the newspaper reporter Fandor (Georges Melchior), whose parents were killed by Fantômas. In order to combat and counteract Fantômas’ schemes, Juve and Fandor have to frequently work under disguise as well (sometimes as Fantômas!), creating complex spider-web plots of intermingling personas and motives. There is never any lawful resolution in the films; Fantômas always escapes justice and is free to create chaos in perpetuity. It’s as if The Joker were the protagonist of the Batman movies.

Fantômas (René Navarre) is a master of disguise, a master criminal, and a ringleader of the underworld. He can insinuate himself into society playing whatever role suits his needs at the time: a lover, a judge, a doctor, a prisoner. He treats his underworld comrades as cavalierly as he does the upper crust, stealing from them with impunity. Determined to catch and bring Fantômas to justice are Inspector Juve (Bréon), of Paris and the newspaper reporter Fandor (Georges Melchior), whose parents were killed by Fantômas. In order to combat and counteract Fantômas’ schemes, Juve and Fandor have to frequently work under disguise as well (sometimes as Fantômas!), creating complex spider-web plots of intermingling personas and motives. There is never any lawful resolution in the films; Fantômas always escapes justice and is free to create chaos in perpetuity. It’s as if The Joker were the protagonist of the Batman movies.

Fantômas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine (1913) introduces the title character as he steals money and jewels from Princess Danidoff in her hotel room, then makes his escape by subduing the bellboy and taking his persona. Then begins an elaborate ruse in which an actor named Valgrand who’s playing the character of Fantômas on stage in a fictional play is drugged, subdued and replaced by the real Fantômas. This episode also introduces Lady Beltham (Renée Carl), whose husband is killed by Fantômas and who becomes Fantômas’ mistress.

Juve vs. Fantômas (1913) is a cat-and-mouse affair wherein Fantômas keeps Juve and Fandor off guard by playing the role of both a doctor and the bandit and gang leader Loupart. Two highlights of this entry are a train robbery and subsequent crash and Juve’s bedroom battle in the middle of the night with a huge boa constrictor let into his window. The entry culminates with Fantômas in full creepy black hood, mask and cape blowing up Lady Beltham’s villa in an attempt to kill Juve and Fandor.

The Murderous Corpse (1913) is the longest of the chapters and begins as the last left off; Juve is missing and presumed dead while Fandor hunts down Fantômas on his own. Fantômas’ scheme is especially dastardly here: he frames an artist for murder, arranges for the artist to be murdered in prison, steals the body and creates a glove from the dead artist’s hand in order to leave the dead artist’s fingerprints behind in thefts. Juve, meanwhile, is undercover as an underground member of Fantômas’ gang of thieves.

Fantômas vs. Fantômas (1914) begins with a newspaper conjecturing that Juve and Fantômas are the same person. Fantômas masquerades as an American detective, the humorously named Tom Bob, criminal Père Moche, and as himself in a fun scene wherein three characters disguised as Fantômas show up at a costume ball (one is murdered).

Fantômas vs. Fantômas (1914) begins with a newspaper conjecturing that Juve and Fantômas are the same person. Fantômas masquerades as an American detective, the humorously named Tom Bob, criminal Père Moche, and as himself in a fun scene wherein three characters disguised as Fantômas show up at a costume ball (one is murdered).

The False Magistrate (1914) is the last and least of the films and also suffers from many missing scenes cobbled together with explanatory title cards. It features uniquely memorable scenes including the death of a Fantômas compatriot left hanging in a church tower bell, with no way down, a murder by escaped gas, and Fantômas’ disguise as a priest. In the end, Fantômas has escaped. There were likely more episodes planned, but WWI intervened, ending not only the Fantômas series, but France’s worldwide domination of the film industry.

To those not familiar with films of the period, Louis Feuillade’s directing will seem primitive. It was. It consists of stationary shots or tableaus, on which the action takes place in long shots as on a stage; only close-ups of objects are used for variation. And yet, freed from the necessity of inter-cutting and the distractions of varied, subjective and competing camera angles, the viewer forgets those embellishments and concentrates on the story; this early directing style is easy to get used to, and can still surprise. In one scene Fandor escapes from a trunk he was trapped in and sits down to rest for a moment — and then is surprised to see a murdered body which was just out of reach of the camera frame. The effect implies an entire world beyond the camera.

The Kino DVD set features prints restored by Gaumont. Scenes are shown in different color schemes for effect. The music score, alas, is stitched together from previously created library tracks. While the main theme conveys the right note of menace and gravity, other cues just don’t work, especially the awkward “happy” music used for Fandor and his newspaper office. It’s a shame a score couldn’t have been newly composed and recorded for an important presentation such as this.

The Kino DVD set features prints restored by Gaumont. Scenes are shown in different color schemes for effect. The music score, alas, is stitched together from previously created library tracks. While the main theme conveys the right note of menace and gravity, other cues just don’t work, especially the awkward “happy” music used for Fandor and his newspaper office. It’s a shame a score couldn’t have been newly composed and recorded for an important presentation such as this.

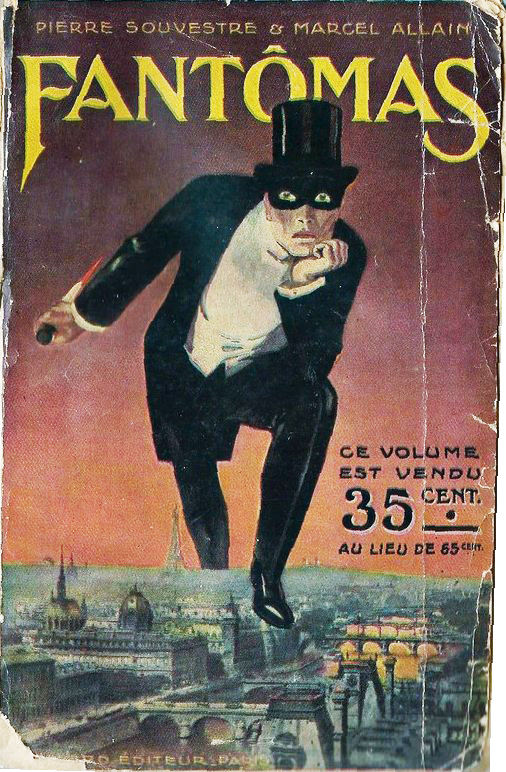

The set also includes a ten-minute documentary on Feuillade, an example of his “Le Film Esthetique” work (The Nativity, 1910), an example of his “Life As It Is” work (The Dwarf, 1912), and a gallery of Fantômas photos and posters, including examples of the way the character’s been used time and again over the last 100 years (there was a Marvel X-Men character created in homage to Fantômas just recently). Topping the presentation off is two informative commentaries by historian and author David Kalat, who not only gives background on Feuillade and his working methods, but explains some of Fantômas’ more recent appearances and reaches backward to detail the long, 19th century history of French crime detection and crime detective fiction, all of which predates Sherlock Holmes by many decades (the Fantômas films were based on a series of novels by French writers Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestrel; there were 42 novels in the series’ original run).

—Michael R. Neno, 2020 August 31