Mr. Wong, Detective

The Complete Collection (1938–1940) ***

Cultural critic Edward Said’s 1978 book Orientalism has become a key work in post-colonial studies. In it, Said analyzes the West’s contemptuous depiction and portrayal of the Orient as a primitive, irrational and inferior society. (On the same day I’m writing this review, Random House announced it was discontinuing the publication of six books written and drawn by Dr. Seuss, at least one of which contains racial depictions which reflect Orientalism). Any cursory glance at popular culture of the 20th century does expose prejudicial portrayals of any and all cultures who weren’t white European power brokers, from Amos and Andy (white actors in blackface) to the buck-toothed “Japs” in WWII U.S. propaganda films.  And yet, portrayals of “the other” were not monolithically prejudiced and contemptuous; how else does one explain the extraordinary popularity of not one, but three Asian detective series in the ’20s and ’30s, series which translated from novels and short stories into movies, comic books, radio shows and TV series?

And yet, portrayals of “the other” were not monolithically prejudiced and contemptuous; how else does one explain the extraordinary popularity of not one, but three Asian detective series in the ’20s and ’30s, series which translated from novels and short stories into movies, comic books, radio shows and TV series?

The template was set by author Earl Derr Biggers’ Charlie Chan. He conceived the character as an anecdote to Yellow Peril fiction characters like Sax Rohmer’s threatening Fu Manchu. Such was the popularity of the Honolulu police detective that nearly fifty feature films were made of the character, who also appeared in comic strips and board games. After Biggers’ death, the Saturday Evening Post published Pulitzer Prize winner John P. Marquand’s Mr. Moto stories, made into a successful detective film series starring Peter Lorre. Hugh Wiley’s Chinese-American detective Mr. Wong stories were published in Colliers Magazine. The San Francisco based Wong was educated at Yale University and is an agent of the United States Treasury Department.

Monogram Pictures, one of the so-called Poverty Row studios known for their small budgets, made the Mr. Wong series films, now released as a complete collection by VCI. For the title role in the first four films, Monogram hired Boris Karloff for the role, who was down on his luck after the decreasing (and temporary) popularity of horror and monster movies. The fact that Karloff was anything but Chinese would now be considered “yellowface” acting. Even accepting that the process of acting involves performing as someone the actor is not, Karloff’s British accent would convince no audience member of his Chinese lineage. Having said that, he gives the character intelligence, dignity and a reserved resilience. In contrast to Wong is Grant Withers as Wong’s associate, Police Captain Street; he’s brash, obnoxious, impatient and often blunder-headed. Though Withers’ role is partly played for humor, it’s noteworthy that the Asian protagonist is the logical and civilized one.

Mr. Wong, Detective (1938), directed by William Nigh, sets the tone. It may be the creakiest of the series, with scenes paced as if stuck in molasses, but I dug the beautifully designed rooms of Wong’s mysterious living quarters. Wong and Street tackle a locked room murder mystery involving an international spy ring. Maxine Jennings plays Street’s girlfriend, Myra, who makes her one and only appearance in the series.

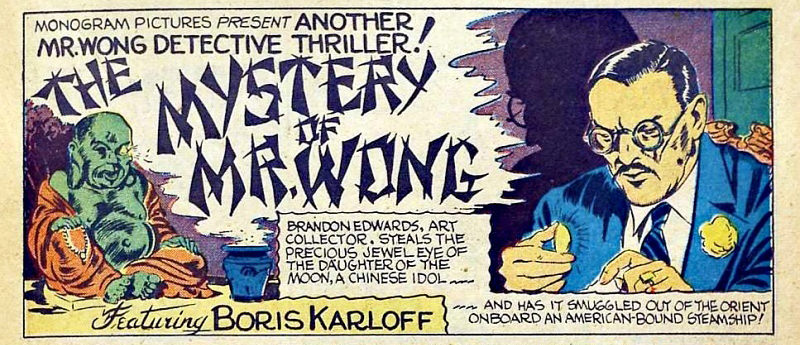

The Mystery of Mr. Wong (1939), also directed by Nigh, involves the theft in China of a priceless sapphire, the Eye of the Daughter of the Moon. The sapphire is stolen again, in San Francisco, its “owner” murdered. The directing, acting and pacing are more confident in this second entry.

Mr. Wong In Chinatown (1939), Nigh directing: A Chinese princess is murdered by a poison dart in Wong’s own living room and the trail to find the murderer involves a mute dwarf and a secret Chinese military mission fighting the Japanese invasion. The entry is noteworthy for the introduction of rambunctious, wisecracking and tenacious reporter Bobbie Logan (Marjorie Reynolds), who gives the series some much-needed humor, in the vein of the then popular Torchy Blane.

The Fatal Hour (1940), Nigh directing: Wong, Street and Logan work to discover the murderer of Street’s police officer friend Dan Grady. The clues lead to a smuggling operation in Chinatown, where Wong’s connections and expertise help the case. This entry benefits from some fine character actors such as Jason Robards Sr. and perennial gangster-playing Frank Puglia (Puglia is one of the few actors who worked for both D.W. Griffith and Peter Falk, on Columbo).

The Fatal Hour (1940), Nigh directing: Wong, Street and Logan work to discover the murderer of Street’s police officer friend Dan Grady. The clues lead to a smuggling operation in Chinatown, where Wong’s connections and expertise help the case. This entry benefits from some fine character actors such as Jason Robards Sr. and perennial gangster-playing Frank Puglia (Puglia is one of the few actors who worked for both D.W. Griffith and Peter Falk, on Columbo).

Doomed To Die (1940), Nigh again: After a fire at sea causes financial disaster for a shipping magnate (Melvin Lang), the magnate is murdered, possibly by his daughter’s fiance. It’s a routine plot, but leavened with humorous banter and a more easy camaraderie between the characters and actors.

Phantom Of Chinatown (1940), directed by Phil Rosen: Rebooting a series (as has been done with Spider-Man at least three times in the last two decades) is nothing new, and the last Wong entry stars an actual actor of Chinese heritage in the role, Keye Luke (better known to today’s audiences as Master Po on the Kung Fu TV series). Luke was in fact the first Asian actor to portray an Asian detective in U.S. film. The milieu is more modern (Wong’s living quarters are modernized), the storytelling breezier. To add to the changes, Wong is given a potential love interest, played by Lotus Long. It’s also smarter about its cultural ramifications. The plot, having to do with a curse on tomb raiders, allows Wong to remark that Western archaeologists looting a Chinese tomb is analogous to Chinese archaeologists digging up George Washington’s grave. It’s a smart jab, unexpected in a film of its time, even considering the Chinese protagonist.

Keye Luke, who before becoming an actor was a longtime Hollywood illustrator, painter and graphic designer, later became more known as Charlie Chan‘s “Number One Son” and got a chance to play the voice of Chan himself in the ’70s animated cartoon series, The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan.

Unlike Charlie Chan, the character of Mr. Wong has receded into obscurity (though he was popular enough at the time to garner his own comic book series). As B movies go, The Wong films aren’t bottom of the barrel, but close. Always looking to cut financial corners, Monogram reused sets in the series and several actors play several roles in the films, almost like an acting troupe. As a snapshot of time and as a look at how foreign cultural identities were being integrated and accepted into American life, the Wong films can be a lazy way to spend a weekend afternoon.

—Michael R. Neno, 2021 Feb 16