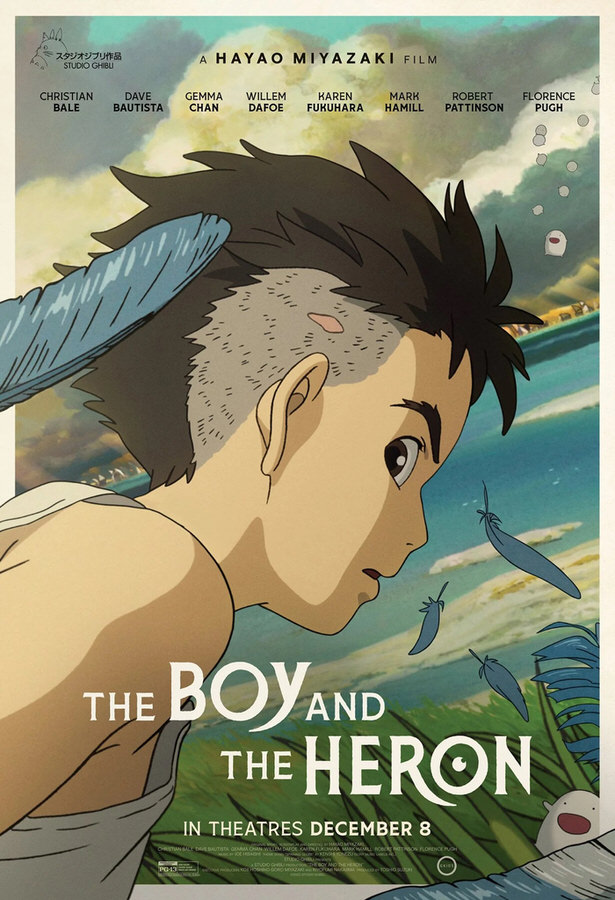

The Boy and the Heron

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (2023) ***

Animation writer and director Hayao Miyazaki is the gift that keeps on giving. He continually announces that each film will be his last, then eventually commences to start another one. When inspiration comes, it’s hard to stop and The Boy and the Heron is even more personal, in some ways autobiographical, than his previous film, The Wind Rises (2013).

Animation writer and director Hayao Miyazaki is the gift that keeps on giving. He continually announces that each film will be his last, then eventually commences to start another one. When inspiration comes, it’s hard to stop and The Boy and the Heron is even more personal, in some ways autobiographical, than his previous film, The Wind Rises (2013).

The Japanese title of the fantastical new film is How Do You Live?, a reference to the 1937 novel of the same name by Genzaburō Yoshino. It begins in the real world, the early ’40s in Tokyo, with young Mahito Maki waking up in the middle of the night: a nearby hospital is in flames. Mahito’s mother, Hisako, is in that hospital and his nighttime race through the crowded streets toward the flames is a hallucinatory nightmare. Hisako dies that night. Eventually Mahito and his father, Shoichi, the owner of a factory manufacturing war planes,  moves to the countryside to live with Hisako’s sister, Natsuko. Shoichi marries Natsuko.

moves to the countryside to live with Hisako’s sister, Natsuko. Shoichi marries Natsuko.

At his new home, quiet but for the gabby antics of seven elderly maids (who may remind one of Snow White’s seven dwarves), Mahito is miserable; in grief for his mother and his forced new circumstances, resentful of Natsuko’s new role in his life, unable to make friends at his new school (his financially privileged status makes him a target for his unruly peers). A large heron first makes its presence known to him, then eventually becomes invasive and taunting and, after weeks, begins to talk. An air of mystery surrounds a nearby dilapidated tower said to have been built by Natsuko’s granduncle. When Natsuko, now pregnant, disappears in the woods, headed toward the tower in a trance, the heron encourages Mahito to follow with him and “rescue his mother”.

The tone of The Boy and the Heron almost unperceptively changes as it takes an Alice in Wonderland-like dive into another world, a picaresque journey in search for Hisako/Natsuko which is so rich in color and visual inventiveness it would be folly to attempt to describe. Viewers who have seen Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo or Spirited Away know the kinds of worlds he can create, but the visions shown here are darker, more inscrutable, more enigmatic: an annoying Birdman hiding inside the heron, hordes of  attacking pelicans, spirits called Warawara who float, lemming-like, into the air to be reborn on Earth, a kingdom of militant parakeets and two surrogates who may or may not be Hisako and Natsuko.

attacking pelicans, spirits called Warawara who float, lemming-like, into the air to be reborn on Earth, a kingdom of militant parakeets and two surrogates who may or may not be Hisako and Natsuko.

If the viewer’s ultimate response to The Boy and the Heron is confusion, that’s not inappropriate. On one level Miyazaki’s not even attempting to construct a story that “connects the dots”. It’s a fantasia that has as its starting points autobiographical details in Miyazaki’s life and his relationships with his collaborators. What the film lacks in logic, though, it makes up for in dazzling, trippy imagery, vivid, almost psychedelic colors and dreamlike resonance. There are scenes in The Boy and the Heron so original and eye-popping, you’ll never forget them. The film, moreover, makes emotional sense even if it uses inscrutable means to arrive there. The film conveys that, through his journey, whether real or imagined, Mahito has made peace with the death of Hisako, and acceptance of Natsuko. The arc is made more acute by the music score, both lifting and mysterious, by longtime Miyazaki collaborator Joe Hisaishi. The list of actors who lent their talents to the English-dubbed version is also formidable: Robert Pattinson, Christian Bale, Mark Hamill, Willem Dafoe, Florence Pugh and Dave Bautista.

—Michael R. Neno, 2024 March 4