The Great Escape

Directed by John Sturges (1963) ***1/2

The Australian WWII fighter pilot Paul Brickhill lived (to the age of 74, in 1991) to see his writings weave into popular culture in surprising and unpredictable ways. His non-fiction 1950 book, The Great Escape, was made into a blockbuster, Panavision movie in 1963 — which itself was the inspiration for the 2000 Aardman Animations movie Chicken Run. Brickhill’s non-fiction 1951 book, The Dam Busters, about the British 617 Squadron, was made into a 1954 film of the same name. The film’s climactic raid sequence was “borrowed” nearly shot by shot, by George Lucas for his attack on the Death Star in Star Wars (1977); Lucas even appropriated dialogue from The Dam Busters for his sequence. Recorded dialogue from The Dam Busters was also incorporated into Pink Floyd’s album, The Wall. Brickhill’s biography of Battle of Britain ace Douglas Bader, Reach for the Sky, was also made into a feature film and another of his books, The Deadline, was adapted for radio.

The Australian WWII fighter pilot Paul Brickhill lived (to the age of 74, in 1991) to see his writings weave into popular culture in surprising and unpredictable ways. His non-fiction 1950 book, The Great Escape, was made into a blockbuster, Panavision movie in 1963 — which itself was the inspiration for the 2000 Aardman Animations movie Chicken Run. Brickhill’s non-fiction 1951 book, The Dam Busters, about the British 617 Squadron, was made into a 1954 film of the same name. The film’s climactic raid sequence was “borrowed” nearly shot by shot, by George Lucas for his attack on the Death Star in Star Wars (1977); Lucas even appropriated dialogue from The Dam Busters for his sequence. Recorded dialogue from The Dam Busters was also incorporated into Pink Floyd’s album, The Wall. Brickhill’s biography of Battle of Britain ace Douglas Bader, Reach for the Sky, was also made into a feature film and another of his books, The Deadline, was adapted for radio.

That’s not bad for a doomed pilot who didn’t know whether he would survive WWII. Brought down over Tunisia by German artillery in 1943, he became a prisoner of war and was eventually sent to the Luftwaffe-run Stalag Luft III, a camp for captured enemy airmen and those prisoners with a history of escape attempts. This is the setting of The Great Escape, a film which director John Sturges, who excelled filming stories involving groups of men, had been trying to convince Brickhill to allow him to make for many years. When he did convince Brickhill to allow the movie to be made, MGM, Sturges’ home base, refused it.  The Mirisch Company fortunately gave it the green light and United Artists released it.

The Mirisch Company fortunately gave it the green light and United Artists released it.

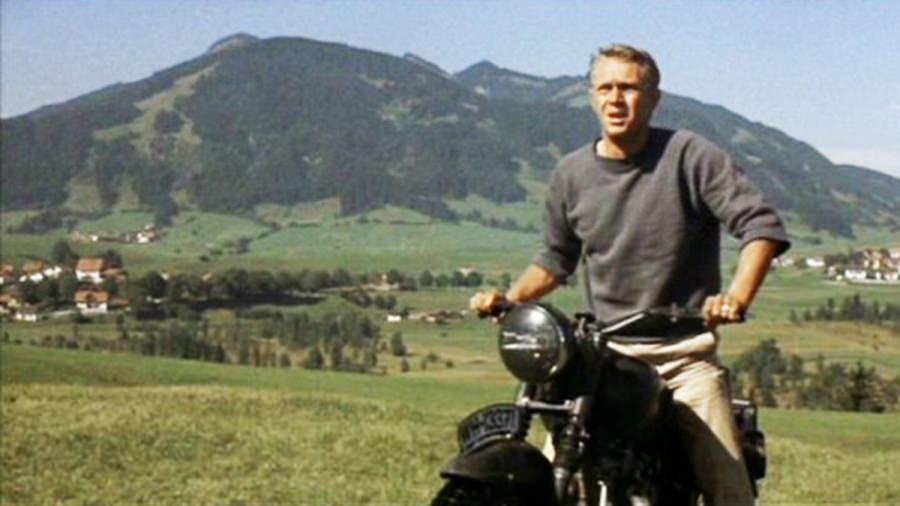

The Great Escape tells the tale of how 76 prisoners were able to escape Luft III, though only three made it to freedom. To tell the story, screenwriters James Clavell (The Fly, Shogun) and W.R. Burnett (Little Caesar, Scarface) simplified/merged real-life characters, added American POWs who didn’t exist, and set the stage for a wide-range of actors and character actors. To name but a few: Steve McQueen (in a star-making role) as the quintessentially American Virgil Hilts (“The Cooler King”), James Garner as Robert Hendley (“The Scrounger”), Richard Attenborough as Roger Bartlett (“Big X”), Charles Bronson as Danny Velinski (the “Tunnel King”), Donald Pleasence as Colin Blythe (“The Forger”), and James Coburn as Louis Sedgwick (“The Manufacturer”).

Big X’s plan is to start work on three deeply dug tunnels leading to the nearby woods, with the goal of freeing 250 prisoners, each with forged documents and civilian clothes. X’s reasoning is that if the Luftwaffe discovers one of the tunnels, one of the other two will suffice. Elaborate techniques for building the tunnels and preparing for freedom are detailed in the film’s leisurely 172-minute running time. Among them: bribing susceptive German officers (the prisoners received Red Cross gifts of soap, coffee, chocolate, etc.), ingenious methods of getting rid of dug-up dirt and shoring up the ceilings of the precarious underground tunnels with wooden bed slats. For accuracy, Sturges hired Canadian fighter pilot Clarke Wallace Chant Floody as a consultant; he had helped implement and dig the Luft III escape tunnels.

As a study in heroism and resolve, The Great Escape is grand entertainment. Even if you’ve already read Brickhill’s book, the film maintains the suspense and adds extra action scenes for box office appeal (McQueen, for example, would reportedly only accept the role if he could show off his motorcycle-riding skills). The Great Escape ultimately has a tragic and historically based sad ending, but the film’s sleight-of-hand somehow allows viewers to leave the film feeling upbeat. If you watch The Great Escape while keeping in mind its lack of historical accuracy, it can still draw you in and keep you riveted.

As a study in heroism and resolve, The Great Escape is grand entertainment. Even if you’ve already read Brickhill’s book, the film maintains the suspense and adds extra action scenes for box office appeal (McQueen, for example, would reportedly only accept the role if he could show off his motorcycle-riding skills). The Great Escape ultimately has a tragic and historically based sad ending, but the film’s sleight-of-hand somehow allows viewers to leave the film feeling upbeat. If you watch The Great Escape while keeping in mind its lack of historical accuracy, it can still draw you in and keep you riveted.

Adding to the atmosphere (and overplaying its hand) is Elmer Bernstein’s musical score, which opens with an upbeat Bridge on the River Kwai-type theme and repetitively hammers home the song in various forms until it becomes another thing to want to escape from. It’s ironic that I’d coincidentally read a 1973 High Fidelity magazine essay by Bernstein the same week I watched The Great Escape — an essay in which Bernstein accused other film composers of the same error.

The two-disc MGM DVD release includes several behind-the-scenes featurettes; an hour-long docudrama, “The Untold Story” (2001), which interviews some of the real prisoners; “The Real Virgil Hilts”, an interview with the pilot, David Jones, who was the basis for Steve McQueen’s character; and commentary tracks.

—Michael R. Neno, 2020 June 22