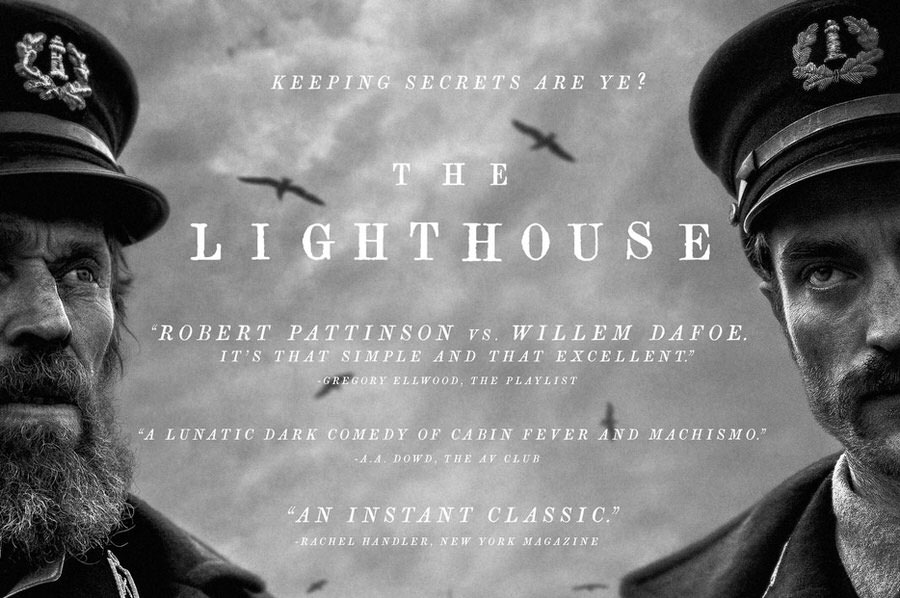

The Lighthouse

Directed by Robert Eggers (2019) ***

For light-hearted, feel-good family viewing, I recommend something other than Robert Eggers‘ The Lighthouse; a warm, cleansing shower might be what you most desire after seeing it. The close quarters of a submarine flick seem spacious compared to the hovel Eggers’ lighthouse keepers hunker in, and when a four-week assignment turns longer (possibly due to a battered and mangled one-eyed seagull) a precarious relationship turns deadly — and then worse.

For light-hearted, feel-good family viewing, I recommend something other than Robert Eggers‘ The Lighthouse; a warm, cleansing shower might be what you most desire after seeing it. The close quarters of a submarine flick seem spacious compared to the hovel Eggers’ lighthouse keepers hunker in, and when a four-week assignment turns longer (possibly due to a battered and mangled one-eyed seagull) a precarious relationship turns deadly — and then worse.

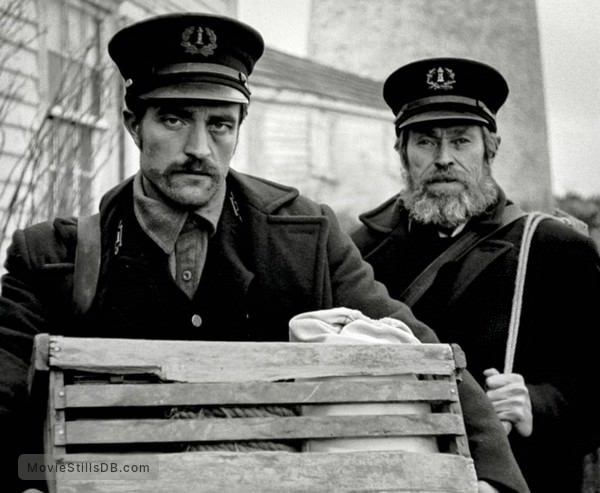

Willem Dafoe is Thomas Wake, a grizzled, demanding, flatulent light-keeper in the late 19th century, mentoring the younger, and taciturn, Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson). Wake works at night, jealously guarding his time in the lantern room, while Winslow is made to do drudge work during the day.  Wake tells fanciful and sometimes contradictory tales of his time as a sailor, while Winslow prefers to remain quiet, keeping his own sordid secrets.

Wake tells fanciful and sometimes contradictory tales of his time as a sailor, while Winslow prefers to remain quiet, keeping his own sordid secrets.

Whatever one may say of The Lighthouse, it’s smartly cast. Dafoe, as an actor, is an American treasure, defiant and ornery and willing to go places other actors wouldn’t (such as his role as the gay, opera listening FBI agent Paul Smecker, in the otherwise unremarkable The Boondock Saints, 1999, and his harrowing role in Lars von Trier’s transgressive Antichrist, 2008). The Lighthouse is no exception. Dafoe hams it up like a character from Melville; Winslow calls him a living parody. Robert Pattinson continues his journey of submerging himself in roles far away from his Twilight series origins. His mustache and serious demeanor recall Daniel Day-Lewis’s Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood (2007). Both actors give their all to bring this story to fruition, under circumstances not much better than their characters live through.

As the drudgery of the weeks go on, Winslow begins to have hallucinatory dreams and visions of a siren-like mermaid, a dead sailor, and sea monsters. The routine of island life begins to truly go amiss after Winslow’s killing of the aforementioned bird, which had been antagonizing him for weeks. Wake believes that seagulls are reincarnated sailors and had told Winslow to leave them alone. It’s after the killing that a horrendous storm appears, making rescue of the two impossible, and with food running out.

As the drudgery of the weeks go on, Winslow begins to have hallucinatory dreams and visions of a siren-like mermaid, a dead sailor, and sea monsters. The routine of island life begins to truly go amiss after Winslow’s killing of the aforementioned bird, which had been antagonizing him for weeks. Wake believes that seagulls are reincarnated sailors and had told Winslow to leave them alone. It’s after the killing that a horrendous storm appears, making rescue of the two impossible, and with food running out.

Shot in a classic 1.19:1 aspect ratio, in B&W, and using vintage ’30s lenses, The Lighthouse attains the look of silent and early sound films. The desolate, sea-surrounded landscapes evoke the B&W films Ingmar Bergman made on the island of Fårö (specifically, Through a Glass Darkly, 1961, which is also a psychological thriller of few characters, culminating in a mental breakdown). The narrow width of the screen also ensures the characters’ faces are often front and center; there’s nowhere in the compositions to hide.

As rations run low and alcohol takes over, the characters’ perceptual connection to reality becomes ever more tenuous, with imagery and allegories from Greek myth, Proteus and Prometheus, incorporated into the narrative. A prerequisite homosexual subtext is also included.

As rations run low and alcohol takes over, the characters’ perceptual connection to reality becomes ever more tenuous, with imagery and allegories from Greek myth, Proteus and Prometheus, incorporated into the narrative. A prerequisite homosexual subtext is also included.

Robert Eggers and brother Max Eggers’ first intentions were to base a story on Edgar Allen Poe’s The Lighthouse but finally only the name remained. Story elements from Melville and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were used; for dialect, they looked to the 19th century novels of Sarah Orne Jewett.

Is The Lighthouse successful in its ambition? The artistry with which the film was made is immersive. The sense of satisfaction and clarity you might feel having watched it, though, is debatable. The Lighthouse is deliberately ambiguous in its third act; this may unsettle some viewers while others will remain intrigued.

—Michael R. Neno, 2021 January 1