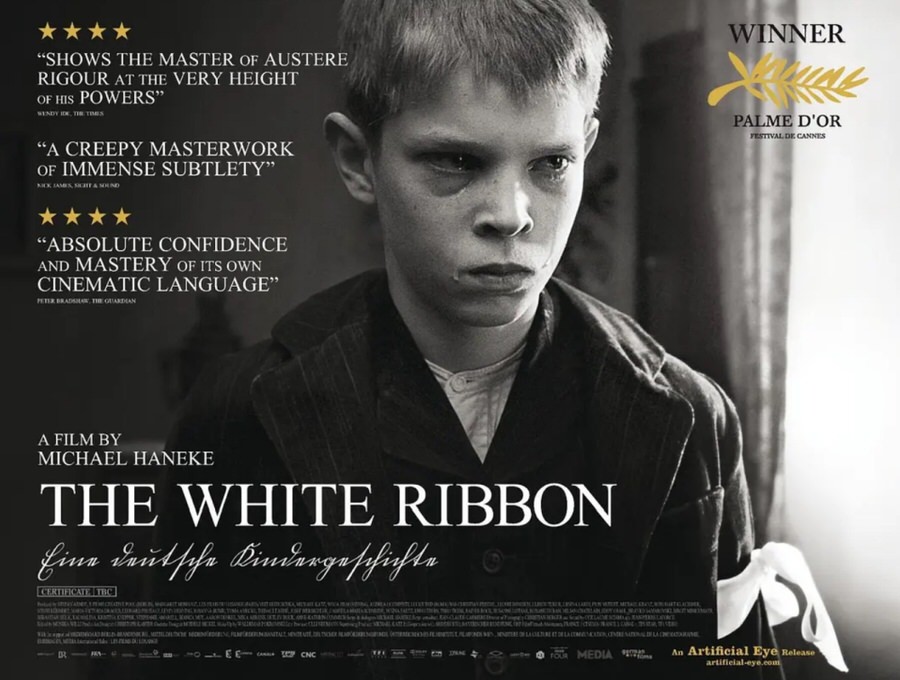

The White Ribbon

Directed by Michael Haneke (2009) ***

In the boundaries between the cruel, Boschian post-WWII absurdities of Jerzy Kosinski and the misogynist-leaning early films and plays of Neil LaBute dwell the works of Michael Haneke, a stern, joyless taskmaster who seems driven to impart lessons about man’s inhumanity to man. In his Funny Games, which he was compelled to film twice (once in German, the second time in English), a family is held hostage by strangers and tortured for no apparent reason. End of story. An ultimately patronizing treatise on the commodification and exploitation of media violence becomes the very thing Haneke is attempting to rail against, medicine which tastes suspiciously like the ailment it’s intended to heal.

In the boundaries between the cruel, Boschian post-WWII absurdities of Jerzy Kosinski and the misogynist-leaning early films and plays of Neil LaBute dwell the works of Michael Haneke, a stern, joyless taskmaster who seems driven to impart lessons about man’s inhumanity to man. In his Funny Games, which he was compelled to film twice (once in German, the second time in English), a family is held hostage by strangers and tortured for no apparent reason. End of story. An ultimately patronizing treatise on the commodification and exploitation of media violence becomes the very thing Haneke is attempting to rail against, medicine which tastes suspiciously like the ailment it’s intended to heal.

Moments of compassion and empathy do sometimes find their way to the surface in Haneke’s work (such as in the otherwise harrowing and extraordinarily depressing Amour, 2012). In The White Ribbon, the narrator, a schoolteacher working in a small, Protestant German village immediately prior to WWI, is the community’s conscience and the film viewer’s connection to rationality (though, even in this character, Haneke leaves open the possibility that the narrator is unreliable).

The schoolteacher, unnamed and played with conviction by Christian Friedel, tells the tale of a series of mysterious and unexplained events, tragedies, that befall the denizens of Eichwald. Many of the villagers work as hired hands for the Baron (Ulrich Tukur). The first person to be bizarrely attacked is the Doctor (Rainer Bock), whose horse is tripped by a carefully placed wire; the Doctor lives, but is sent to a hospital to recuperate. The Baron’s son is gone missing and when found has been severely beaten. A farmer’s wife is found dead, either by accident or murder. The doctor, meanwhile, back from the hospital, commences sexually molesting his daughter and hatefully berating his housekeeper/mistress. The schoolteacher suspects (but has no proof) that the children of the local Pastor (Burghart Klaussner), who he raises in a strict, puritanical fashion, are the culprits behind the town’s mean-spirited events.

The schoolteacher, unnamed and played with conviction by Christian Friedel, tells the tale of a series of mysterious and unexplained events, tragedies, that befall the denizens of Eichwald. Many of the villagers work as hired hands for the Baron (Ulrich Tukur). The first person to be bizarrely attacked is the Doctor (Rainer Bock), whose horse is tripped by a carefully placed wire; the Doctor lives, but is sent to a hospital to recuperate. The Baron’s son is gone missing and when found has been severely beaten. A farmer’s wife is found dead, either by accident or murder. The doctor, meanwhile, back from the hospital, commences sexually molesting his daughter and hatefully berating his housekeeper/mistress. The schoolteacher suspects (but has no proof) that the children of the local Pastor (Burghart Klaussner), who he raises in a strict, puritanical fashion, are the culprits behind the town’s mean-spirited events.

The schoolteacher’s courting of the young Eva (Leonie Benesch), nanny to the Baron until she’s fired, is the only healthy relationship presented in the film, but in one key scene it’s implied that even she doesn’t completely trust her fiancé.

The two-and-a-half-hour tale is carefully and intricately paced, shot in various German locales where the icy winter weather can be best made use of. The locales also fit the style of Haneke’s work, here in black and white: cold and icy. Though the plot and themes aren’t explicitly spelled out, it becomes clear Haneke is arguing, in part, that strict, tyrannical orthodoxy, taught cruelly and without compassion or empathy, helps create and raise those most susceptible to fascism. It’s a juicy bit of irony that so much of Haneke’s work uses similar tactics to “teach” his audience.

A touchstone one might consider as an antecedent to The White Ribbon is Henry Bellamann’s novel Kings Row (1940), revealing the sordid sadism and horror behind a small, quiet town.  A more recent and cinematic influence is clearer, though: Ingmar Bergman’s austere and emotionally raw 1963 Winter Light, taking place in a small rural Swedish village. A vicious and demeaning monologue The White Ribbon‘s Doctor gives is remarkably similar to a dressing down given by the Pastor in Winter Light. That Pastor is played by Gunnar Björnstrand, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the Pastor, Burghart Klaussner, in The White Ribbon. Also pertinently, cinematographer Christian Berger, before shooting The White Ribbon, studied the work of Sven Nykvist, who photographed Winter Light.

A more recent and cinematic influence is clearer, though: Ingmar Bergman’s austere and emotionally raw 1963 Winter Light, taking place in a small rural Swedish village. A vicious and demeaning monologue The White Ribbon‘s Doctor gives is remarkably similar to a dressing down given by the Pastor in Winter Light. That Pastor is played by Gunnar Björnstrand, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the Pastor, Burghart Klaussner, in The White Ribbon. Also pertinently, cinematographer Christian Berger, before shooting The White Ribbon, studied the work of Sven Nykvist, who photographed Winter Light.

There are worse influences to look to than one of Bergman’s best films, and Haneke does maintain a simmering suspense, delving into the private lives of both those who abuse their power and those abused. While its theme is universal, and not tied to a specific time and place, Haneke’s willfully superior tone won’t be accepted gratefully by many film viewers.

—Michael R. Neno, 2022 Apr 11