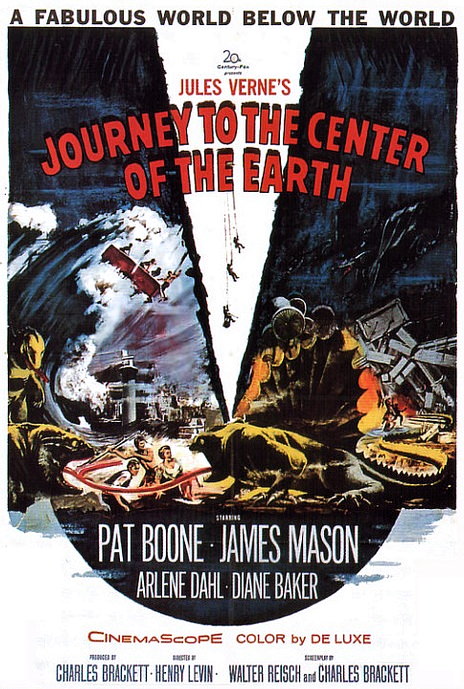

Journey to the Center of the Earth

Directed by Henry Levin (1959) **1/2

20th Century Fox’s 1959 CinemaScope adaptation of Jules Verne’s famous novel is beloved by film watchers who saw it on its first release or saw it at a young age in reruns. In this regard, I come to the film at a disadvantage, as I’m seeing it for the first time as an adult and having just read a recent and faithful translation of the novel.  The book, in my estimation, fares much better.

The book, in my estimation, fares much better.

When author and producer Charles Brackett was tasked with bringing the novel to screen, he thought it “a delightful book, written for young people”. This is the first way the film goes astray. Verne didn’t write Journey for a young audience; it was only marketed that way in the U.S., in poorly edited and translated — in effect, butchered — editions. (In fact, Verne would have included even more adult material — sex and violence, as well satire of French society — in his novels if his publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, had allowed it.) The novel has its whimsical moments, but Brackett’s determination to treat the material as lightweight, with comedy relief, songs and romantic subplots (and more indiscretions that I’ll describe) is contrary to the story Verne told.

Brackett keeps the 1880s time period, but moves the story from Hamburg to Edinburgh, Scotland, where geologist Professor Lindenbrook (James Mason), has just been knighted. As a gift, student Alec (Pat Boone) gives the professor a rock made of lava. Lindenbrook finds an inscription inside the rock written by explorer Arne Saknussemm, who claims he found a passage to the center of the earth and tells how to get there. Gone from the novel is Lindenbrook’s days-long attempt to decipher runes written in code on a piece of old paper.

The film then creates two villains the book had no need for: 1) Professor Göteborg (Ivan Triesault) who attempts to steal Lindenbrook’s discovery and is soon murdered by 2) Count Saknussemm (Thayer David), Arne’s descendant, who also wants to retrace his ancestor’s journey. Göteborg’s widow, Carla (Arlene Dahl), insists on descending into the earth with Lindenbrook, Alec and an Icelandic strongman, Hans (Peter Ronson).

The subterranean sequences are a mixed bag. Three and a half million dollars were spent in the making of the adventure, and the scenes utilizing matte paintings were both state of the art and quite beautiful, even haunting. The underwater sea, with its vast beaches and cavernous “sky” is especially striking. Some of the underground scenes were filmed in Carlsbad Caverns. Too much of the film, unfortunately, looks (to these perhaps jaded eyes) sadly stage bound.  Though Verne’s novel was ultimately far-fetched (which says nothing about its many qualities), it feels realistic while reading it. The pitch-black tunnels our heroes traverse in the book, lit only by Ruhmkorff coils, are claustrophobic, vivid, tactile and frightening. Much of the film, however, takes place in absurdly brightly lit sets, which took me out of the story and far too aware of the set designers. There’s the giant mushroom set, the salt set, the precarious bridge set, the crystal lake set, etc., all looking too much like the studio space they were created in. The prehistoric creatures of the novel are here iguanas shot up close. The journey ends at the lost city of Atlantis, another sequence created exclusively for the movie.

Though Verne’s novel was ultimately far-fetched (which says nothing about its many qualities), it feels realistic while reading it. The pitch-black tunnels our heroes traverse in the book, lit only by Ruhmkorff coils, are claustrophobic, vivid, tactile and frightening. Much of the film, however, takes place in absurdly brightly lit sets, which took me out of the story and far too aware of the set designers. There’s the giant mushroom set, the salt set, the precarious bridge set, the crystal lake set, etc., all looking too much like the studio space they were created in. The prehistoric creatures of the novel are here iguanas shot up close. The journey ends at the lost city of Atlantis, another sequence created exclusively for the movie.

The film of Journey to the Center of the Earth was modeled after Walt Disney’s 1954 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Both feature James Mason as the lead. Both feature needless songs inserted. (There were originally many in Journey, most of which were fortunately cut. There’s still plenty of dancing and frolicking, singing, accordion playing and marching bands to go around, though.) Both feature pet animals for the kiddies (a sea lion in Leagues, a duck in Journey). 20,000 Leagues is, on the whole, the better film and one of the best Verne adaptations.

Better than the script, and quite effective, is composer Bernard Herrmann’s score, with its use of ominously low organ chords, working on an almost subliminal level.  It gives the film a heft and magnificence its visuals don’t always provide.

It gives the film a heft and magnificence its visuals don’t always provide.

Screenwriter Walter Reisch said of his work on Journey, “When they bought the Jules Verne novel from his estate and assigned me, I was delighted. The master’s work, though a beautiful basic idea, went in a thousand directions and never achieved a real constructive ’roundness’.”

I believe the opposite is true: Verne’s novel had a constructive “roundness”, and it’s the 1959 film that “went in a thousand directions”. Certainly, with a novel long in the public domain, there’s room for many interpretations (it was even the basis of an ABC Saturday morning cartoon, with Mary Tyler Moore‘s Ted Knight voicing Professor Lindenbrook). I would love, though, to see an adaptation faithful to the novel. As is, the ’59 film will continue to enthrall those who view it nostalgically and those who haven’t read the novel, and the underground sequences could, I imagine, entertain the young even today.

—Michael R. Neno, 2019 November 4